Back in February, I wrote a piece

for The Guardian that

told some of the history behind the record. More of the tale appeared in this

month's issue of Record Collector magazine, but the whole

story has not been told until now. It's a long read, but if you're interested

in the truth behind the incredible Kay,Why? then grab yourself

a cuppa and read on.

For LGBT people, and especially for gay

men, the summer of 1967 offered much promise. The new Sexual Offences Act

(which introduced some of the recommendations of the decade-old Wolfenden

Report) had just been passed, meaning that homosexuality – well, homosexual

acts between two consenting adult males aged over 21, in the privacy of their

own home at least – was no longer a criminal offence, and the atmosphere was

filled with a palpable sense of change for the good. Hippies in kaftans with

flowers in their hair walked the streets of London barefoot, and around the

world people were protesting for equal rights and an end to war. Love was

indeed in the air: the Beatles told a global television audience that it was

all we needed, and it felt like the world believed them.

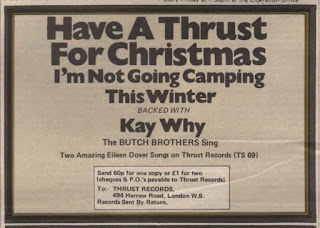

As the summer of love turned first into

autumn and then winter, a strange little record issued by a tiny, London-based

independent label appeared. Very few copies were sold, but it has gone on to

become one of the most sought after, and highly cherished, examples of

typically British camp humour. Its origins have been debated in books, online

and in academic papers, but for more than half a century no one has known the

true identities of the musicians behind this disc, with their Beatle-y ‘ooohs’

and camp archness.

There is a fairly

good chance that the men behind Kay, Why? had heard of

California’s Camp Records, a label that issued a dozen ribald,

under-the-counter singles and two albums between 1964-65. Claiming to employ

the talents of ‘Hollywood TV and screen personalities’, they also used silly

pseudonyms to hide the identity of writers and performers – Byrd E. Bath, the

Gay Blades, Sandy Beech, Rodney Dangerfield (no, not that Rodney

Dangerfield) – and the titles of their releases, including Homer the

Happy Little Homo and Florence of Arabia leave little

to the imagination. But Kay, Why?’, and the flip, I’m Not

Going Camping This Winter, owe more to the British school of campery than

its US cousin.

The disc was the only release from

Thrust Records (fnarr fnarr), based at 494 Harrow Road, London. Now a flat

above a fast food takeaway, at that time it was also the address of Eyemark

Records, a tiny independent record label that had previously issued I

Got You by Sheil and Mal, a Sonny and Cher parody from actors Sheila

Hancock and Malcolm Taylor, and the album Recitals are a Drag by

legendary drag ball organiser Mr. Jean Fredericks. To add to this eclectic

roster, in December 1966 the company announced plans to launch Railwayana

Productions, a series of field recordings of train sounds, an odd and

potentially suicidal move considering that the Beeching cuts were in full swing

and steam was being replaced by diesel.

Eyemark (or Eye Mark as it

occasionally appeared) was set up by Mark Edwards, a former BBC cameraman who

was moving into music video production, and Malcolm Taylor, an actor, stage

director and acting coach. Taylor also ran, with his actress mother Margaret

Taylor, an employment agency, Domestics Unlimited, providing work for ‘resting’

actors and musicians, and one of the musicians he was finding work for was Eric

Francis, singer with a four-piece psychedelic rock group from Fulham, the

Purple Barrier. ‘It was a good way to earn a little money when we didn’t have any

gigs,’ says Francis. It was through Taylor that Francis met Edwards and

introduced him to the rest of the group (Francis and Purple Barrier drummer

Alan Brooks had previously been in The Wanted, with David Bowie’s future guitar

maestro Mick Ronson), and Edwards quickly became the band’s booking agent and

de facto manager.

.jpg) The Purple Barrier recorded one

(unreleased) single for Eyemark before, in 1968, changing their name to the

Barrier, to avoid any confusion with Deep Purple, friends from the same part of

London, who had just issued their debut 45, Hush!. In the spring of

1968, the Barrier issued their first single, Georgie Brown,

co-written by Mike Redway, who the previous year had sung the closing theme for

the James Bond spoof Casino Royale, Have No Fear, James

Bond is Here. Georgie Brown was backed with a song that

has gone on to become a psychedelic classic, Dawn Breaks Through,

composed by Francis and bandmate Del Dwyer. ‘”Georgie Brown” was absolutely

horrendous,’ says Francis. ‘We didn’t want to do it and it didn’t represent

what we sounded like. It did nothing over here, thank goodness, but it proved

popular in some other countries, which meant that we had to go and do TV shows

to promote it in places like Belgium and Germany. We absolutely hated it!’

Booked to appear on a TV show in Belgium, the band were horrified to find brass

instruments laid out for them to play. ‘It had an oompah-band backing,’ Francis

explains. ‘There were tubas and trumpets and god knows what in the middle of

the floor of the studio, and they expected us to play them. We were just a

four-piece pop band! We were on the show with the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, and

they were so talented, they picked these instruments up and they were away. We

ended up miming to the record, and they played alongside us.’

The Purple Barrier recorded one

(unreleased) single for Eyemark before, in 1968, changing their name to the

Barrier, to avoid any confusion with Deep Purple, friends from the same part of

London, who had just issued their debut 45, Hush!. In the spring of

1968, the Barrier issued their first single, Georgie Brown,

co-written by Mike Redway, who the previous year had sung the closing theme for

the James Bond spoof Casino Royale, Have No Fear, James

Bond is Here. Georgie Brown was backed with a song that

has gone on to become a psychedelic classic, Dawn Breaks Through,

composed by Francis and bandmate Del Dwyer. ‘”Georgie Brown” was absolutely

horrendous,’ says Francis. ‘We didn’t want to do it and it didn’t represent

what we sounded like. It did nothing over here, thank goodness, but it proved

popular in some other countries, which meant that we had to go and do TV shows

to promote it in places like Belgium and Germany. We absolutely hated it!’

Booked to appear on a TV show in Belgium, the band were horrified to find brass

instruments laid out for them to play. ‘It had an oompah-band backing,’ Francis

explains. ‘There were tubas and trumpets and god knows what in the middle of

the floor of the studio, and they expected us to play them. We were just a

four-piece pop band! We were on the show with the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, and

they were so talented, they picked these instruments up and they were away. We

ended up miming to the record, and they played alongside us.’

With his connections Edwards was also

able to get the Barrier included on a pilot for a new BBC pop show, featuring

Julie Felix, and had them slated to perform the title song for a film starring

Terry-Thomas and Phyllis Diller, The Pubs of London, which was

never made. Georgie Brown did well enough for Philips to sign

the band, with Eyemark and Mark Edwards staying on as producer.

Could Mark Edwards be Eileen Dover,

or perhaps one of the two singers featured on the disc? Edwards was a man

fizzing with ideas, many of which would involve his own small circle of gay

friends. As well as running his record label, he was also working on a music

video project for TV broadcast around the world, filming acts associated with

songwriters Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley, including Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick

& Tich, and The Herd. The giant Philips corporation offered financial

backing for the project, and Edwards produced clips for several Philips acts,

including Dusty Springfield, Manfred Mann and Esther and Abi Ofarim. When not

on tour, Francis would often get involved in the filming, and he and Edwards

worked on a number of projects together, including the Bee Gees’ television

film Cucumber Castle. ‘At one point, we were probably doing 60

or 70 percent of this country’s pop promotion films,’ Francis states. ‘The kind

of thing they would show on Top of the Pops when the band were

not available.’

With companies in Japan working on a

viable home video system, Edwards and his backers were discussing how they

could make these half-hour music compilations available to home consumers,

almost a decade before domestic video players became available. When Philips

withdrew their backing, Howard and Blaikley stepped in, forming a new company,

Video Supplement, with Edwards. Their first project together – announced in

February 1971 - was to be a half-hour special entitled the Festival of

Light. That does not appear to have been successful, however they did

produce one programme, Europop, in early 1972 that featured The

Electric Light Orchestra, John Kongos Lindisfarne, Mott The Hoople, and Slade.

As well as participating in Edwards’

video project, Howard and Blaikley were also involved with Eyemark Records,

writing Uh!, the A-side of the Barrier’s second single, and debut

for Philips, as well as the follow-up, Tide is Turning. Their

distinguished, decades-long careers include two UK number ones, Have I

the Right? for The Honeycombs (produced by Joe Meek) and The

Legend of Xanadu for Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich (for which

Edwards and Francis shot the promotional film), as well as more outré material

with a decidedly queer theme. They even wrote for Elvis. I contacted Ken and

Alan to ask if they knew anything about Kay, Why?’, but they

informed me that neither of them was involved.

That might have been the end of it,

but, just a few days before Christmas 2021, I was contacted by Eric Francis,

lead singer, occasional fire eater, and one of the principle songwriters for

the Barrier. Eric told me that it was they who provided the instrumental backing

for Kay, Why?. ‘At the time of recording we had no

idea what it was for other than the fact it was for a comedy record,’ he

recalls. ‘Mark Edwards was responsible for the production and distribution, but

he had nothing to do with writing or performing on it. Howard and Blaikley,

although they were connected with us as a band, had nothing to do with it

either.’

Kay, Why? was recorded in early November

1967 at Olympic Studios, Barnes, where just a few months before the Beatles had

put down the backing track to the anthemic All You Need is Love,

and its B-side Baby, You’re a Rich Man. Other acts including Led

Zeppelin, Queen, the Rolling Stones and David Bowie would also use the studios

before they closed their doors in December 2009. The Purple Barrier performed

on the instrumental track for Kay, Why?, but were not involved with the vocal. After finishing the session,

they were off to Europe on tour. ‘We were told it was for a comedy record,’

says Francis. ‘There was no fee involved, we just did it as we were all mates,

and we were missing by the time they came in to do the vocals.’

So who wrote the songs and performed

vocal duties on the disc? ‘It was written and performed by Roy Cowan and Iain

Kerr,’ says Francis. ‘They were a talented duo who, in the late 60s and early

70s, performed as “Goldberg and Solomon”, a comedy Jewish version of Gilbert

and Sullivan. Iain also played piano on “Georgie Brown”, and he’s on “Shapes

and Sounds” and the Howard and Blaikley song “Uh!”. He was just a nice chap who

was always around. Iain and Roy were at the session, but they didn’t record

their vocals at the time. No one was more surprised than we were when we

finally got to hear it!’

Not long afterwards, while Barker and

Kerr was performing at a London night club – ‘The kind where you pay five

shillings for a glass of water and extra for the glass’, he later recalled –

they were introduced to Roy Cowan. Cowan, born in Hampstead, London of Russian

parents, had trained to be a rabbi but discovered his knack for writing

parodies of hit songs while serving in the army. The budding song satirist, who

had previously written lyrics for Charles Aznavour among others, impressed Kerr

with an on-the-spot parody of Moon River, entitled Chopped

Liver, and an immediate, and lasting, partnership was formed. As well as

working with Cowan, Kerr continued to perform in clubs and hotels in London,

becoming friendly with visiting US stars including Bob Hope and Sammy Davis

Jr., and was regularly featured on the popular BBC radio programme Music

While You Work.

The pair wrote songs for Kerr’s

nightclub act as well as for other artists, including both sides of the 1966 45

issued by septuagenarian cabaret singer Miss Ruby Miller, Daphne Barker’s aunt.

They also wrote My Poem For You, the B-side to Mike Redway’s James

Bond single, and Cowan wrote the lyrics for the huge international hit A Walk

in the Black Forest. Perhaps the most bizarre commission came from tractor

manufacturer Massey Ferguson, who had the pair compose a full opera for the

company, that was staged in a corn field in Greece in front of sales delegates

from around the world.

‘We met Mark Edwards and Malcolm Taylor

at a recording session for Philips,’ Kerr explains. ‘They liked what we were

doing and asked if we had anything else. I said, “well, we’ve got this song

called “Kay, Why?”, but we need a backing group. That’s how we got the Purple

Barrier. They were very good, but the Brothers Butch were terrible! The band

were very good, very professional, and Mark and Malcolm both liked “Kay, Why?”

so we let them get on with it and didn’t ask questions. We had a very friendly

relationship with the boys, and thought that they were trying their best.’ With

no promotion, sales of ‘Kay, Why?’ were tiny, but it was for their unique take

on Victorian light operetta, Gilbert and Sullivan Go Kosher, that

Cowan and Kerr would achieve international fame.

As Goldberg and Solomon, the pair

recorded their first album, for Edwards and Eyemark, the same year as the Butch

Brothers tracks were laid down. The Tailors of Poznance (subtitled the

Best of Goldberg and Solomon, Volume Two) featured actress Miriam Karlin,

star of the hit TV show the Rag Trade, who Kerr had

coached for her role in the hit stage musical Fiddler on the Roof.

Karlin also recorded a pair of Howard and Blaikley numbers that year for

Eyemark, which were licensed to Columbia. Various sources have suggested that

the pair had intended to issue a prequel – The Chandeliers: the Best of

Goldberg and Solomon, Volume One – but Kerr denies this. ‘There never

was a Volume One,’ he laughs. ‘Gilbert and Sullivan’s first opera

failed [the music for Thespis is now lost]; they didn’t have a

“number one”, and we decided that we would not have a “number one” either.’

Kerr was also involved in another

Eyemark release around the same time: QPR – The Greatest, performed

by Queens Park Rangers footballer Mark Lazarus. ‘I did it because I was

asked!’, he says. The flip side features what is probably the most peculiar,

psychedelic football anthem ever recorded, a song called Supporters -

Support Us, credited to the Q.P.R. Supporters, of which, says Francis, ‘I

have heard it suggested many times that it may be something to do with us, but

not guilty!’ A third Barrier single, again produced by Eyemark for Philips, was

issued when the company demanded a follow up to Uh!. Howard and

Blaikley produced The Tide Is Turning, a track from the latest Dave

Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich album, and Edwards provided the B-side, A

Place in Your Heart, but although the Barrier recorded the vocals, none of

the band actually played on the disc: ‘The tracks were laid down while we were

on tour in Germany,’ Francis explains. ‘We came back and we were told “this is

your next single”!’

Very little – if anything – was done to

promote Kay, Why?, and by December 1967 Cowan and Kerr

were in Johannesburg, with their show An Evening With Goldberg and

Solomon. Kerr recalls the trip well. ‘Roy and I went out to South Africa on

the ship the Windsor Castle,’ he adds. ‘Halfway through the journey were

invited to drinks at the Pig and Whistle, the crew’s bar. They had decorated

the bar out for us, and as we went in there were two fellows miming to our

“Kay, Why?” record!’

By 1970 Eyemark was no more, but by

that time, Edwards had already moved on. ‘For a while I took over the office,’

says Francis. ‘I was running an entertainment agency, Amberlee Artists, with a

guy called Ray Perrin.’ Francis had left the Barrier, who would continue on for

another couple of years with a different vocalist. ‘It was all very amicable,’

he explains. ‘In fact, I was at the audition to replace me. They found a guy

called Ian Bellamy… He was a very good singer. Better than I was!’ Francis made

one more single with Howard, Blaikley and Edwards, the bubblegum novelty Alcock

And Brown, credited to The Balloon Busters, but by now Edwards had signed a five year

production contract with MCA records for a husband-and-wife team he managed,

John and Anne Ryder, and the pair scored a hit in several overseas territories

with the Marty Wilde/Ronnie Scott-penned I Still Believe in Tomorrow.

The Eyemark back

catalogue was taken over by a new company, Amberlee Records Limited, headed by Eyemark’s former

sales manager John Peters (initially based at the same address: in 1973 they

would move across the road

from the former Eyemark offices), who would continue the railwayana series and

expand into organ recitals. sadly the company chose not to reissue Kay, Why?

Edwards’ hit his peak as a producer

in 1970, with Curved Air’s debut album Air Conditioning; that same

year Eric Francis managed to score a number one hit in Japan, with the band

Capricorn, and another song from the team of Wilde and Scott, Liverpool

Hello, but apart from the occasional session (including one for soul singer

Doris Troy, then signed to the Beatles’ Apple label) that would be his last

shot at stardom. ‘By 1971 I had a small baby, and I decided to get out. I had

been a professional musician for about ten years,’ he says, ‘But I would have

been better off financially stacking shelves in Morrisons. I did some driving

for a car hire company; one of my customers was Greg Lake, the bass player with

Emerson, Lake and Palmer, which was a bit embarrassing because he was a mate!’

Edwards would later manage (well, mismanage would be more accurate) gay

singer-songwriter Steve Swindells, who in turn would go on to work with

Hawkwind and Roger Daltrey among others. ‘Mark Edwards was beginning to drink too much

by the time we split from him,’ says Eric Francis. ‘He died quite a few years

ago after throwing away what could have been a good career.’

A few years ago a peculiar digital

release turned up on Amazon and iTunes, coupling both sides of Kay,

Why?’ along with the very similar sounding The Girls In the

Band and Bald, a pastiche of Age of Aquarius,

the hit song from the free love musical Hair. This MP3 EP also

included three other songs, one of which was Waltzing with Hylda,

from Cowan and Kerr’s mid-70s revue Slightly Jewish and Madly Gay. Credited to the daisy Chain Duo,

Kerr now admits that the performers are Cowan and himself. ‘Roy and I went to

see the Boys in the Band [it opened at Wyndham’s Theatre,

Leicester Square, in February 1969], and I had coached Oliver Tobias for his

role in Hair.’ The plan had been for a second Brothers Butch

single, but this did not materialise. ‘Roy and I were extraordinarily busy at

the time,’ he recalls.

Indeed they were. During the decade

following the recording of ‘Kay, Why?’, Goldberg and Solomon recorded three

further albums and toured the world, playing several return seasons in

Australia and South Africa and appearing in front of more than 1,000,000 people in more than 200 venues. The curtain fell on their highly

successful act when Cowan died of a heart attack, aged 54, in Sydney in June

1978; at that time the two men had been working on a musical based on the life

of Ruby Miller, alongside her niece Daphne Barker. That same year Malcolm

Taylor - the actor who co-founded Eyemark Records and later teamed up with

Howard and Blaikley to write a novelty single for actor Wilfred Bramble - gave

up acting and songwriting for a seat in the director’s chair. He would go on to

direct many episodes of TV serials, including Coronation Street, Crossroads and EastEnders.

Taylor died in January 2012. The Barrier’s drummer Alan Brooks is no longer

with us, neither is guitar player Del Dwyer (Brooks and Dwyer would both later

become members of cult r’n’b band the Downliners Sect) who sadly passed away at

the end of December. Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley continued to have a massively

successful, if somewhat eclectic, career and are both still around today, and

records by the Barrier have become some of the most sought-after from the

British psychedelic era: a copy of Georgie Brown in its

ultra-rare picture sleeve sold in 2020 for over $1,500.

Kay, Why? appeared at a time when LGBT

people in Britain were beginning to find their voice. It may not have changed

the world, but despite its commercial failure, it is an important footnote in

the history of LGBT music. ‘We were aware,’ says Kerr, ‘That we were sticking

our oars out and making a few ripples.’ Those ripples would soon become waves.

Super research on a fascinating article. Thank you!

ReplyDelete